Many people have analyzed the movie, The Shining, coming to various conclusions regarding what they think this movie is really about. I’d like to offer a somewhat different interpretation. Mine will build from a foundation of two very good analyses that I’ve seen, one given by Joe Girard in Eye Scream. and the other being Kubrick’s Gold Story, parts 1 and 2, by Rob Ager, though neither of these come to the same conclusions I do.

This is analysis is also available on YouTube: https://youtu.be/YTF-oNGlw5o

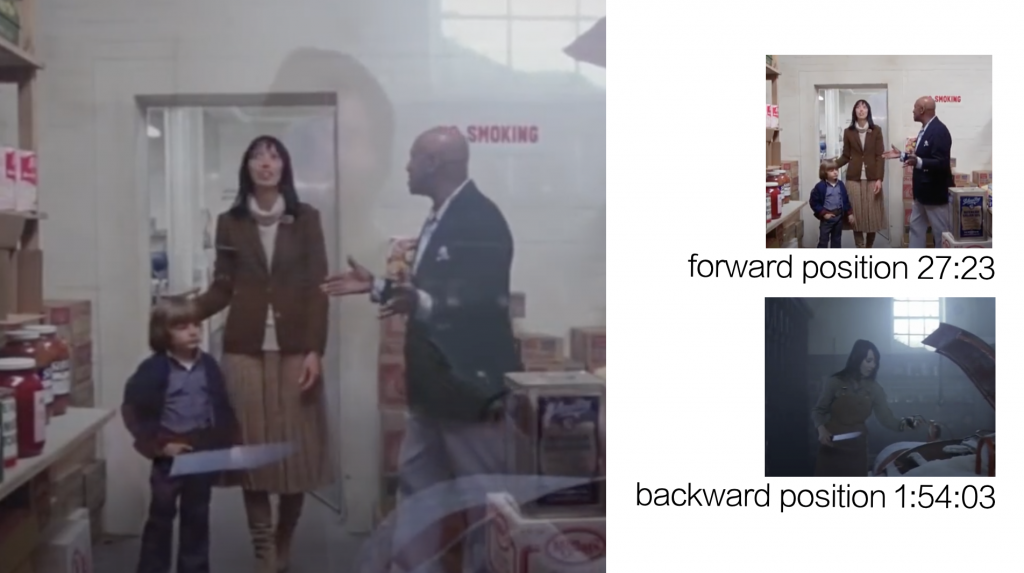

Joe Girard’s Eye Scream revealed the fact that there are several synchronicities that show up when you play The Shining forwards and backwards at the same time, like the one below, when the overlay seems to put Wendy’s knife from a scene near the end of the film into Danny’s hand near the movie’s beginning. Girard credits John Fell Ryan and Mastermind with the idea to overlay the film backwards and forwards, and he calls this overlay the “mirrorform.”

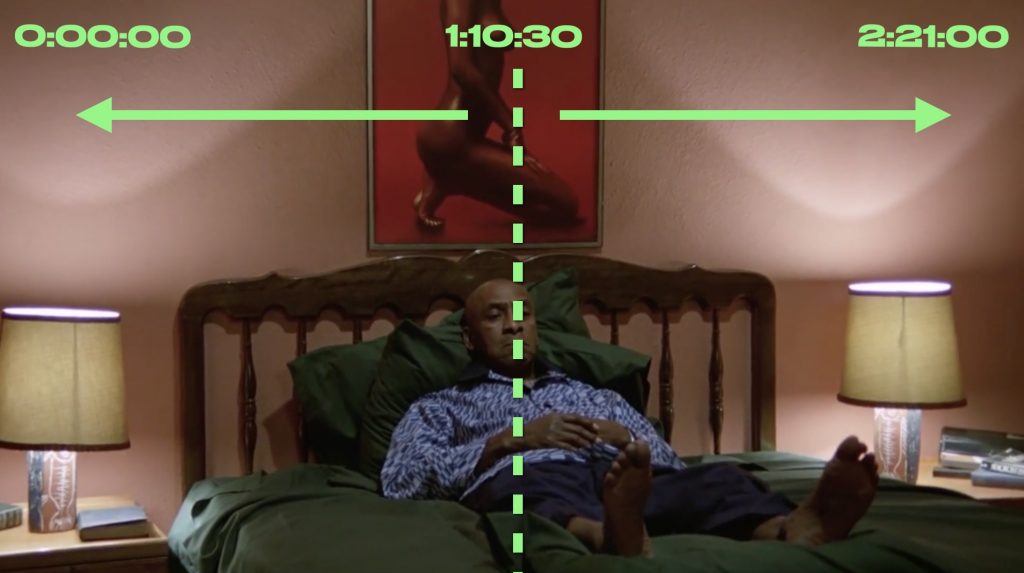

Looking at the film in this way places emphasis on the film’s exact center, what I would call the film’s mese, a term from the ancient Greek used in music to describe the center of a certain scale, or the central string of a lyre. I find a lot of meaning, both symbolically and structurally in the concept of the mese or the center, and I find the mese symbolism and structure at work in The Shining — especially when the mese is ever so slightly off.

But looking at the mese or midpoint of a story has never been a normal part of literary criticism. For that, we’ve always used the story arc, which breaks a plot line into three basic sections with two turning points. So when I saw that Girard was dividing The Shining’s story up differently, I was intrigued and have used this overlay technique of the mirrorform to explore the film in a new way for myself.

The Gold Room

Rob Ager’s two-part analysis called Kubrick’s Gold Story was my first introduction to a possible hidden meaning regarding the hotel’s Gold Room. Ager explains some of Kubrick’s personal views about banking corruption, as well as the importance of the gold standard.

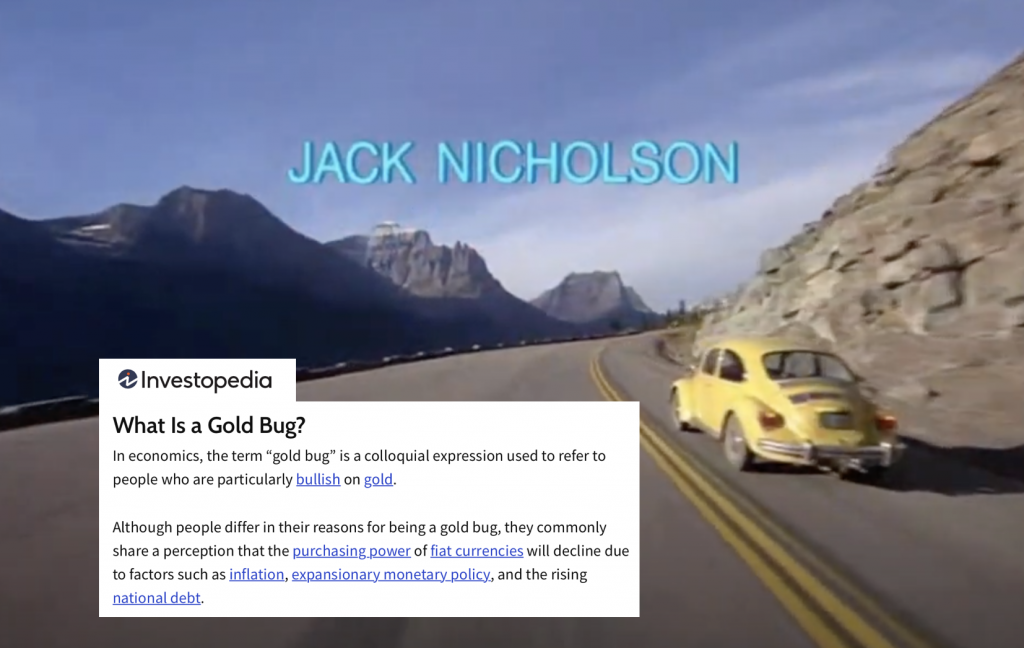

Ager points out that Kubrick owned gold and also recommended gold to his friends. On hearing this, I realized that Kubrick was a “gold bug,” a well-known economic term describing someone who views gold as a store of value, a way to hedge against the depreciating value of the dollar, and this may have been the reason he changed the family’s red Volkswagen beetle to a yellow one.

Ager then draws our attention to Lloyd, the bartender, who tells Jack — in the Gold Room — that his credit is fine, but his money is no good here. Jack’s money is 1980 fiat currency, meaning that its value, its purchasing power, is debased or impaired. Jack’s money isn’t worth very much.

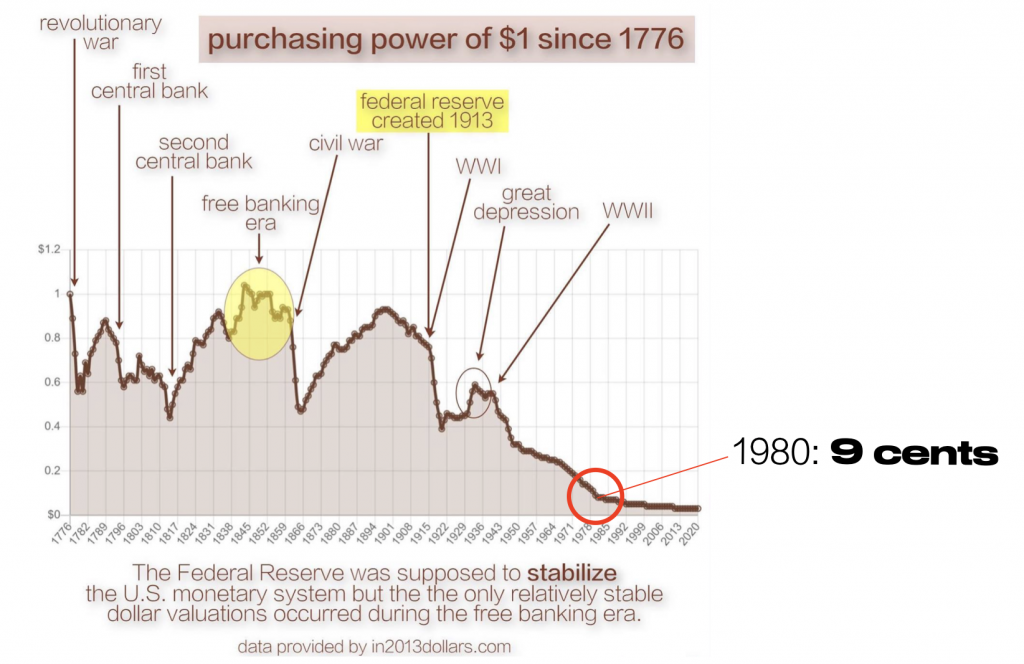

I made this graphic several years ago with data from in2013dollars.com to show the loss of the dollar’s value since it was established in 1776. Looking at this chart, we can see that although Jack’s dollar in 1980 was legally defined as worth one dollar, the true worth of a 1980 dollar was around 9 cents.

In 1921, when this party in the Gold Room was taking place, US dollars were still valued using the gold standard, and although the Federal Reserve had been inflating the currency, a 1921 dollar was still worth about 40 cents, quite a bit more than a 1980 dollar, and so — Jack’s money was “no good here.”

Notice in this graph that there’s only been one time in the US dollar’s history that it’s been worth more than one dollar. That was during the free banking era around 1840. Also notice that every single time the dollar takes a nose dive, one of two things is happening: either a central bank begins operations, or a war is started.

Ager supports his analysis of the Gold Room with a scrapbook prop used briefly in the film that he was able to study at the Kubrick Archive. Many of the articles Kubrick pasted into the scrapbook were, according to Ager, concerned with WWI, the creation of the federal reserve, and the gold standard. Building from Ager’s analysis, I’d like to offer my own interpretation of The Shining as it relates to monetary gold.

In my book, The Next Octave, the gold standard is a central theme. The gold standard was an aspect of metallism, a system of money either holding intrinsic value (like gold or silver) or backed by a supply of value (like a gold standard) and it’s the gold standard that prevents a government or a private bank from debasing its paper currency by inflating the money supply. Inflating paper dollars is easy — you simply print more of them. But if each dollar is linked to a weight of gold, inflation is no longer easy to do because you can’t just print more gold.

Why would a government or a bank want to debase its currency? To steal its value. When a currency is debased, its value is lowered. A visible way to do this is to clip off some bullion from a gold coin. The person doing the clipping has just stolen some gold and the value of that coin will be lower now, after it’s weighed by a cashier or money changer. However, a LESS visible way to debase a currency is simply to inflate its supply: scarcity increases value, so making units of money less scarce, or more plentiful, also makes them worh less.

Since 1913, the Federal Reserve has inflated the US money supply, which is a form of taxation — or, really, ciphoning — that nobody realizes is taking place. We can see in the graphic above that the value of the dollar has continually fallen, with a few brief corrections, since 1913.

The tax of inflation enriches the elite — the best people who normally stay at the Overlook Hotel — while it impoverishes or lowers the purchasing power of individual consumers, the type of people who normally work, rather than play, in the Overlook’s Gold Room.

Although Ager points out that there was no Gold Room in King’s novel, I did find many examples of monetary metaphor and allusion there, lines like:

Their quarters were filled with counterfeit sleep.

His eyes were like small silver coins.

The snow had stopped and a silver-dollar moon had peeked out through the raftering clouds…

In addition to silver, Stephen King used gold imagery as well:

Jack stood in a dusty ingot of sunlight, which slanted through the dirty window — a commentary on the gold bars of Jack’s world: based on a shining light, but dusty and dirty and completely intangible.

And this one: Everything he touched seemed to turn to gold . . . except the Overlook.

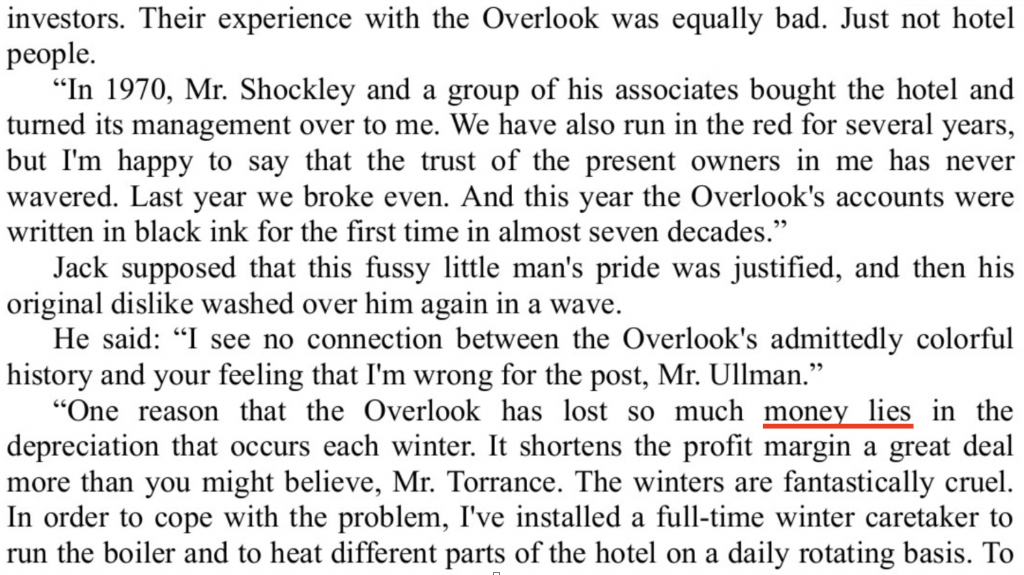

This line referred to one of the later owners, a corrupt businessman named Horace Derwent. And according to Ullman, one reason that the Overlook had lost so much money lies in the depreciation that occurs each winter, a monetary term that refers back to the depreciating dollar in our corrupt monetary system. I especially like the positioning of the phrase “money lies” in the novel:

And I think this movie, both as written by King and filmed by Kubrick, is communicating a message about true money and false money — money that shines and money that lies. Money that shows you its worth, and money that lies about its depreciating value, still insisting that a dollar is worth a dollar (when it’s really only worth nine cents).

Money that lies, that depreciates as a result of inflation and war, is mentioned outright by King in the novel, when the woman sitting next to Halloran on the flight back to Denver refers not once, but TWICE, to dollar diplomacy as the cause of America’s dirty little wars.

And it’s not the elites, but the people who suffer when governments debase currency through inflation and war. When a dollar is worth less, it has a weaker purchasing power, something that’s really important to consumers, especially the common man. To them, the purchasing power of the dollars in their pocket determine their survival and that of their families. This could be why Jack initially looks concerned when told that his money is no good.

Here we see him grimacing at the worthless paper in his hand.

We see a lot of paper in the Shining, but usually in the form of books, piles and stacks of them, even the hotel scrapbook, and all of these books represent information or stories written down as an act of work, the economic act of production and the same type of “playless” work that Jack appears to be doing at his typewriter.

But Jack’s story exists in contrast to all these books in the film because he’s not at work. He’s not producing anything of value. He’s producing the insane repetition of a single sentence, much like paper money’s value is falsely and insanely repeated as it’s printed and re-printed. Even more interesting is that Jack is typing on paper that isn’t white — it’s a greenish yellow, that almost looks like the paper on which the dollar’s darker green ink is printed.

In Jack’s single sentence, he repeatedly describes himself as a “dull boy,” admitting over and over that he lacks shine. A dull boy would be, literally, a dullard, and etymologically, that word is interchangeable with the word dollard, “a nickname for a dull or stupid person.”

A paper dollar is also dull, especially in comparison with the shining surface of gold. Might this sentence, “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy” be revealing Jack’s realization that working for this dollar is keeping him mentally dull and tethered to the dollar’s lack of shine? Might he slowly be realizing that he’s trapped, not only in the snowed-in Overlook Hotel, but also in a no-win, debt-based monetary system?

Jack’s deteriorating mental state is what most critics pick up on in their analysis of the film, but I think an important aspect of his state of mind is financial, creating the same no-win psychological state that occasionally drives men to kill their families.

The red book on Ullman’s desk isn’t Carl Jung’s Red Book, as many claim, but we do know Kubrick was very infuenced by Jung and Jung writes about gold in the Red Book as something that shines. And in light of the film’s definition of shine — an ability to know other’s thoughts or premonitions of the future, i.e., to have knowledge of the true nature of reality — this seems to suggest that shining gold represents a form of truth. In economic terms, its value is intrinsic and obvious to the observer, a true form money in an economy saturated with false money.

When Jack is in the Gold Room, but has no money in his wallet, he tells Lloyd he’s “light.” In his paper poverty, Jack becomes light, and shines. In fact, when Jack says this, his face is underlit by the bar, a light that’s further magnified by the bar’s mirrors. Without false paper in his wallet, Jack is moving toward monetary truth.

The passage in the Red Book, in which gold shines, reveals a strange nature of gold as money. Carl Jung hears the voice of Philemon discussing gold in the following way: “I want to turn you around. I want to master you. I want to emboss you like a coin. I want to do business with you. One should buy and sell you. You should pass from hand to hand. Self-willing is not for you. You are the will of the whole. Gold is no master out of its own will and yet it rules the whole, despised and greedily demanded, an inexorable ruler: it lies and waits. He who sees it longs for it. It does not follow one around, but lies silently, with a brightly gleaming countenance, self-sufficient, a king that needs no proof of its power. Everyone seeks after it, few find it, but even the smallest piece is highly esteemed. It neither gives nor squanders itself. Everyone takes it where he finds it, and anxiously ensures that he doesn’t lose the smallest part of it. Everyone denies that he depends on it, and yet he secretly stretches out his hand longingly toward it. Must gold prove its necessity? It is proven through the longing of men. Ask it: who takes me? He who takes it, has it. Gold does not stir. It sleeps and shines. Its brilliance confuses the senses. Without a word, it promises everything that men deem desirable. It ruins those to be ruined and helps those on the rise to ascend.”

The strange nature of gold is that, for all its power, it remains passive. It has no will of its own and, therefore, can’t be described as either a force for good or bad. Its nature is to simply shine, to simply tell the truth.

A Hopi elder named Antonio Mirabal, also known as Mountain Lake, spoke with Carl Jung in Taos, New Mexico in 1925. The Hopi are the westernmost tribe of the Pueblo people. He told Jung that the Hopi people saw the white man as “mad.” And this passage in the Red Book might help in explaining why the white man is so plagued by the panic and fear that induce madness: the fact that everyone “anxiously ensures that he doesn’t lose” his gold would lead us to conclude that if the elites have stolen society’s gold, the result might be a level of anxiety, of panic, a mental madness that’s collective, society-wide, all based on a grand financially-based cognitive dissonance.

Ullman tells us that the construction of this pleasure palace for the elites started in 1907 on land that was formerly an Indian burial ground, and that construction workers had to fend off physical attacks from the Native Americans. Their land ownership hadn’t been codified in a contract, and contracts were one mechanism of manifest destiny that allowed the theft of land from indigenous tribes to take place. In fact, contracts are a theme of The Shining (show a clip of verbal contract).

But there was clearly a dispute over the ownership of the land under the Overlook Hotel and the builders of the Overlook were, in the eyes of the Native Americans, engaged in an act of theft.

Construction on the Overlook began in 1907, a year mentioned twice by Mr. Ullman, so it might be useful to know what was going on monetarily during that year. The most obvious event was the Panic of 1907, a run on banks that was triggered when the president of Mercantile National Bank in New York attempted to corner the copper market. In Ullman’s office we see two plaques that look to be in the shape of arrowheads: one is gold, the other is copper.

In the resulting Panic of 1907, banks began to collapse and both the government and J.P. Morgan became involved in a series of bank bail-outs. According to the website Federal Reserve History, it was the Panic of 1907 that led to the creation of the Federal Reserve, whose purpose it was to stabilize the banking industry and prevent the need for such bailouts. It would seem that the Federal Reserve has failed in this original purpose, something Kubrick, as a gold bug, would be well aware of.

It’s a modern stereotype that ancient Indian burial grounds spawn hauntings of the buildings built over them. But the ghosts of the Overlook Hotel were never shown to be indigenous peoples. These ghosts were white, 20th century Americans: a hotel caretaker, a bartender, a lawyer’s wife, two young sisters, a man in a tuxedo, his costumed companion, and a group of wealthy party-goers from the 1920s. The evil isn’t coming from the buried Ute tribe that once roamed throughout Colorado, but from the white man, who grows increasingly anxious trying to defend against an incremental, continual, and pervasive depreciation of the purchasing power necessary to his survival.

When we hear about a man killing his family, the reason given is rarely cabin fever; it’s almost always financial. But The Shining isn’t just a story of upstairs/downstairs, rich versus poor, owner versus caretaker. This is a story about financial terror, something I think Kubrick saw as a very real threat to human survival, something worthy of a horror film.

The terror comes about not from a single, traumatic event, a one-time mugging or murder in a dark alley, but from the ongoing theft of society’s wealth as a whole, especially the gold supposedly of Ft. Knox that many suspect isn’t really there.

The year of the film’s final photo, 1921, was also the year the government’s general accounting office was created, and one of the functions of the GAO has been to audit the gold reserves at Fort Knox and the Denver Mint. The storage of gold in Ft. Knox metaphorically correlates to the Overlook’s storeroom in which stacked boxes are marked Golden Rey. Rob Ager noticed the fact that the storeroom’s locks are somewhat over-engineered. But both the kitchen storeroom and the Gold Room house valuable commodities that require insurance, perhaps because the elites present at the Overlook have been in the habit of gleaning a percentage of Golden Rey off the top.

A few years before The Shining was released, the GAO performed an audit on the gold reserves in Ft. Knox. In this 1977 audit, it was reported that some of the gold was tested and found to be not as pure as it was supposed to be, meaning it had been debased. The impurity was blamed on improper melting and casting of the melts in 1920 and 1921, the same year the fictional picture at the Overlook was taken of people that Rob Ager believes were originally involved in the formation of the Federal Reserve. Were they celebrating an imperfect melt and debasing of the gold that wouldn’t be noticed for another 56 years?

Gold purity is measured in karats. and pure gold contains no other metals, coming in at 24 karat. The first level of gold debasement, in which the gold purity is reduced from 99.9% to 98.7%. We see these purity values in two medieval Italian coins, the florin and quartarola. The florin is fully pure at 24 karats, but the next purity level down, the quartarola, measures in at 23.7 karats, a number that holds some importance in the film.

Room 237 is adorned with gold-striped wallpaper, and this room corrupts and debases. The room number represents the first tier of gold debasement, and anyone pure and innocent, like Danny, anyone who shines the truth will be debased if they enter. For Danny, that’s a just a bruise because it’s just the first LEVEL of debasement, though, ironically, we sometimes call a bruise a shiner.

In The Shining, the thieves creating financial terror for everyone else are the bankers, politicians, and royalty — the “best people” — the hotel guests, the party-goers, the cabal.

Here, most analysts of the film believe the man on the left is wearing a bear costume, relating to Danny’s bear pillow, suggesting sexual abuse. But I don’t see the face of a bear.

I think this costumed person represents the Golden Boar, a symbol of power and wealth in both Norse mythology and Indonesian folklore, a symbol that’s evolved into our modern piggy bank. In the novel, it was Roger in a dog costume servicing Derwent, one of the later and more corrupt owners of the hotel. But using a boar costume in the movie, Kubrick may be suggesting that the removal of the gold standard and the debasement of the currency has reduced the symbol of the Golden Boar to cheap polyester fur and plastic teeth, forced into a humiliating position of servitude pleasing the cabal.

Of course, it’s Wendy who fulfills the caretaking responsibilities, but that doesn’t change the fact that these financial pressures exist and create a level of anxiety in Jack’s psyche, in a way that’s very similar to the anxiety of the Panic of 1907, a financial terror that caused many people to anxiously ensure they didn’t lose their savings — that’s what a bank run is all about — but that also caused several bankers to commit suicide. Currency debasement, even at just 23.7 karats, can produce a psychological terror because it’s an actual threat to our survival.

And its the film’s focus on anxiety and panic that makes me think there’s a possible connection between The Shining and a relevant court case concerning an injured victim named Halloran. I can’t really even suggest that Kubrick or King knew about this case, but its parallels are somewhat uncanny. Perhaps it’s another case of the collective unconscious at work.

But before we look at the court case, I want to dwell for a moment on how Halloran is absolutely central to this film, literally. Girard’s mirrorform shows that the camera’s on Halloran at the exact mese of The Shining. In the bedroom, Dick Halloran lies centered (though slightly off-center) on the bed between two sets of framing lamps, reminiscent of the two columns of Solomon’s Temple that we also find in freemasonry.

I bring up freemasonry for a couple reasons. Speculative freemasonry was reborn under the guidance of Sir Francis Bacon, who used his great intellect to develop cryptic ciphers. Symbolism was a language used cunningly by both Bacon and Kubrick, and both men lived in St. Albans outside London: Bacon in Gorhambury and Kubrick just a few miles and a few hundred years away in Childwickbury.

It’s from the the Greek mese or meson that the English word mason derived, primarily because the freemasons relied on the mese in traditional methods of laying brick. And the masons would frame the mese with the two pillars of Solomon’s Temple that we see adorning masonic lodges, columns known as Joachim and Boaz. These two pillars represent light and dark, the sun and the moon — a gold and silver imagery we also see in King’s novel.

These columns are also known as the Pillars of Hercules, located at the mouth of the Mediterranean, and Joe Girard spends some time in Eye Scream unpacking all the allusions to Hercules in The Shining, noting, above all, that in a moment of madness, Hercules had murdered his wife and kids.

Another example of two-pillar imagery in the film is the Grady twins who stand as two pillars blocking the room’s EXIT and suggesting there’s “nothing further beyond,” just as the pillars of Hercules did at Gibraltar. That their heads are encompassed in the mirrorform by a gold lampshade suggests that we may see other sets of pillars in the form of lamps.

These allusions to Greek mythology and masonic columns are interesting, but why would Kubrick go to the trouble to include them in the film? I think, again, that he was symbolizing money, as the two pillars evolved into our modern-day dollar sign. The Spanish piece of eight featured two pillars, and because it was Spanish, the letter S with the two pillars struck over it, began to symbolically reference this coin.

If the Joachim column symbolized silver, it might not be a stretch to suggest that the Boaz pillar was connected to gold, more specifically the golden field of barley belonging to the biblical Boaz, from which the poor were able to glean grain — a play on the common idiom that though gold is extremely valuable, you can’t eat it. Of course, both gold and silver are edible but the purity of edible gold must be between 23 and 24 karats, and a common karat value of gold foil and gold flake is, again, 23.7 karats, the first level of debased gold.

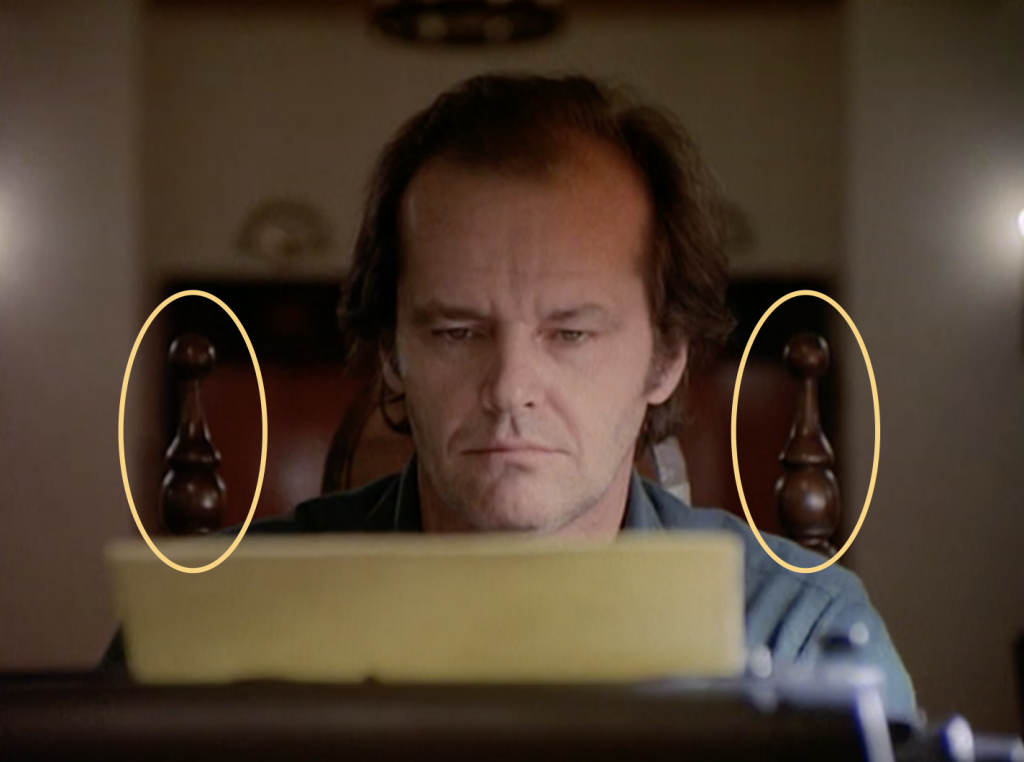

And notice that as Jack types away, he’s the mese between this same, money-centric, two pillar symbolism, and between which he produces reprint after reprint of no value at all.

But let’s return to the relevant court case. It involved a woman named Catherine Halloran, who was injured through the negligence of her employer, the New England Telephone and Telegraph company. A few other hints that this case is relevant to The Shining occur in the case heading: it’s heard by the Vermont Supreme Court, in the year 1921, and it carries the case number of 273, what Joe Girard would call a “jumble” of 237.

Halloran v. New England Telephone was a tort case, in which Halloran sought monetary damages for mental suffering as a result of New England Telephone’s negligence. The case went to the Vermont Supreme Court and Halloran won. But what’s really fascinating, and relevant to the themes we’ve been exploring in The Shining, are the majority and dissenting opinions in the case.

First, it had to be determined if Halloran’s mental distress and anxiety qualified as legal mental suffering, and therefore eligible for tort compensation. The majority opinion of Justice George Powers stated that, “It is to be observed that mere regret, disappointment, or vexation are not mental suffering within the meaning of the rule, but fear, worry, and apprehension are typical sorts of it. And it is very properly held that the anxiety must be natural and not speculative, real and not fanciful.” The case also describes examples of mental anxiety that legally qualify, the list sounding like something straight out of a horror movie: “fear of hydrophobia, apprehension of insanity, dread of blood poisoning, fear of giving birth to a deformed child, and dread of death from swallowing gláss, are admitted as proper elements of damage.” It was determined that Halloran was legally owed tort compensation, as “her mental anxiety and distress… [was] a proper element of recoverable damages.”

This is relevant to The Shining because extreme mental anxiety has been inflicted, not only on Danny and Wendy, but much more so on Jack. His anxiety level has risen quickly at the Overlook and is pushing him toward the same kind of mental break that Grady experienced. And this court case is arguing that such anxiety can carry a monetary value, that, in the interpretation of tort law, inflicting this kind of anxiety on another person creates a FINANCIAL debt — not surprising in our debt-based monetary system.

Pertaining to the monetary value of anxiety, we read this: “Counsel for the plaintiff [Halloran] was allowed to urge in argument, that in assessing the damages the jury should consider the present impaired purchasing power of the dollar.”

Remember, this case was argued in 1921, and this graph shows the value of the dollar at this time — between 1913, when the Federal Reserve was formed, and 1920, the dollar’s value had just dropped 40 cents. This is the impaired purchasing power of the dollar that the court case refers to. And this 40 cents on every dollar is what the government, through the elites at the Federal Reserve, had just stolen from the people. I think Kubrick was rightly illustrating here that this system would produce a great level of financial anxiety, the kind that can and does tear families apart.

The decision holding for Halloran was written by Justice Powers of the Vermont Supreme Court, and articulates the true nature of our fiat currency into the court record: “Necessarily, damages are to be expressed in terms of money. And while money is the standard of value by which the worth of all other property is to be measured, and while, in theory, its value remains constant and unfluctuating, and while it must be admitted that really it is prices which rise and fall amid changing economic conditions, yet, after all, in a very real and a practical sense money itself is a shifting standard, varying in value according to the changes in its purchasing power… So it is that, at least so far as those elements of damages properly classed as pecuniary losses — like loss of time, loss of earning power, expenses and the like — are concerned, it is proper for the jury to take into consideration the fact, known to everybody, that the purchasing power of money is at present seriously impaired. And it is so held by the courts.”

But wait a minute: in 1921, the US was still on the gold standard, so why did the dollar’s purchasing power weaken in the first place? Doesn’t a gold standard prevent this kind of inflationary expansion?

The answer is that during World War I, most countries suspended their gold standard in order to finance their war efforts. The US didn’t fully suspend theirs, but they didn’t fully honor it, either. Dollar to gold convertibility was still in place during WWI, but obviously that couldn’t last and loopholes were devised.

The government raised a ridiculous amount of money for World War I through debt, and by ridiculous I mean that their borrowing history went from $200 million in 1898 to $21.5 billion in 1917 and 1918.

The 21.5 billion dollars was raised by selling Liberty Loan gold bonds to the public. The advertising campaign pushing Americans to buy them was emotional and intense. The bonds stated that, “The principal and interest hereof are payable in United States gold coin of the present standard of value.” But shortly before it came time to pay back these bonds, the country was forced to end gold convertability and President Roosevelt outlawed the ownership of gold. The reason for this was that the U.S. simply didn’t have the gold reserves with which to pay the people back, despite the existence of the Federal Reserve and all its promises to stabilize the currency. Rather than admit they didn’t have the gold, they simply outlawed its possession by the public, a move that conveniently replenished some of the gold the government had given to the elites.

What the Great War allowed was a transfer of gold from the public over to the “best people,” the elite families who made their fortunes from wartime activities: DuPont (gunpowder), Vanderbilt & Astor (transporting military supplies), and Rockefeller (fueling the war), in addition to several others not mentioned in the guestbook of the Overlook Hotel. Of the four presidents Stephen King listed in the novel, three of them had a devastating influence on the gold standard, the most obvious being Nixon. The public bought bonds in gold-backed dollars and were repaid in depreciated paper while the best people pocketed the gold.

But the government did something else during World War I that allowed the elites to make another hidden profit: it placed strict limits on exporting gold out of the US. This was basic mercantilism: the economic belief that a country’s supply of gold should remain inside its borders, and that gold’s value is somehow separate from the value of the commodities it buys (a policy first debunked by Francis Bacon in New Atlantis). But this ban on gold exports created a black market for gold smuggling that removed legitimate export competition and created a gold export monopoly for the elites.

And it was done, as it’s been done for centuries, by treating gold as an embellishment to cloth. Historian Anton Howes writes of this process being done in the early 1600s, when goldsmiths, trying to skirt the laws of England prohibiting the export of gold, were hiding it in exported wares as decoration, especially in the form of gold thread embroidered into clothing. Howes notes that, “it appears that their stitches used far more gold and silver than was necessary for the decoration.”

The goldsmiths would process gold bullion into gold thread and hide it in plain sight, weaving it into book bindings, clothing, and rugs. The thread was first wound onto spools that were then UNwound as they were sewn into various textiles. (photo of Gold Room sign). And the Overlook Hotel’s proximity to Sidewinder could be a play on words that the winding and unwinding of gold thread was a side gig.

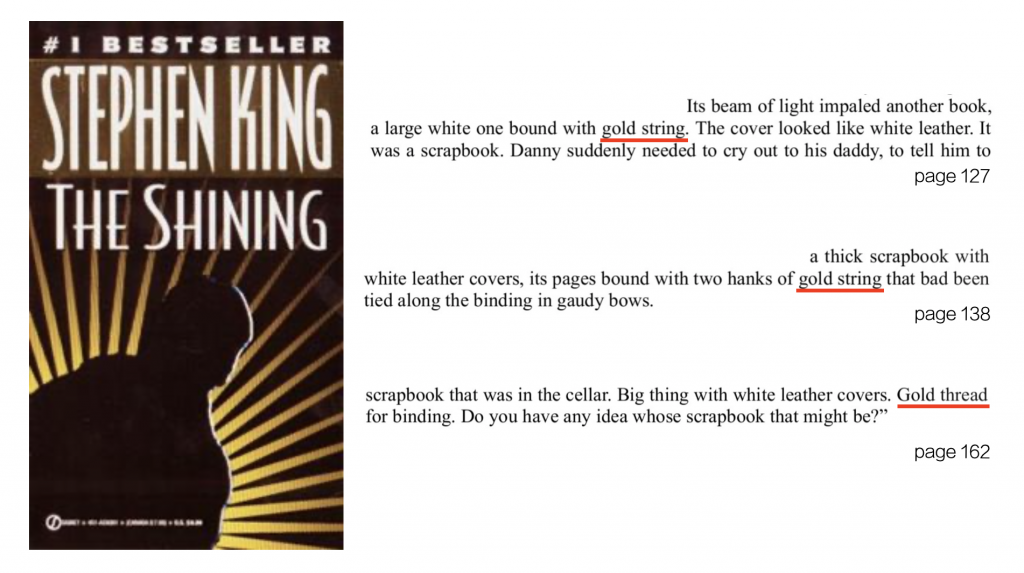

Several hints in King’s novel suggest that the illegal exportation of gold thread was going on at the Overlook Hotel. First, King draws our attention to gold thread three times in his description of the hotel scrapbook’s binding.

Next, he describes the ballroom rug, seen in the film removed as Ullman shows Wendy and Jack the Colorado Lounge, as having gold embroidery, and golden “tracings.” And finally King tells us in the novel that there are various corrupt and illegal business dealings going on, especially during the hotel’s ownership by Horace Derwent. This was euphemistically described as, men from New York who were apparently doing more in the Garment District than making clothes.

Mr. Derwent had two relevant “investments” — five textile mills in New England and a bankrupt cropdusting company he turned into an airmail service. Bottom line: Derwent had the capability to transport textiles out of the country.

In the film, I see the Gold Room of the 1920s holding space for the ghosts of elites who found a way around the gold standard, both inflating the money supply to ciphon gold, while also smuggling processed bullion out of the country.

But there’s a bit more. In Eye Scream, Girard shares the synchronicities that are also to be found when you overlay the Beatles’ Abbey Road three times over the course of the film. The album runs about 46 minutes 50 seconds, and if you’re watching the Shining with the 11-second Warner Brothers ID at its beginning, you can start Abbey Road at zero minutes, twelve seconds, again at 47:01, and finally at one hour, 33 minutes and 52 seconds. The album will end with about 30 seconds to spare at the end of the film.

The audiovisual gems found here aren’t covered well in a blog post, but the relevant lyrics include:

“Golden slumbers fill your eyes…

boy, you’re gonna carry that weight…”

“Writing fifty times I must not be so, oh, oh, oh…

and when she turned her back on the boy, he creeped up from behind…”

“You never give me your money,

you only give me your funny paper…”

So, if I had to wrap this up into a simple, singular idea, I think that Jack and the axe (a dull, grey metal) bring death to the gold metal that shines. Jack Torrance represents the dollar. A torrent is an overwhelming rush of water, the inflation, oversupply, the flood of a current or currency. Jack becomes more dull and more gray, like the metal of his axe, until his last reflection on the dull mirror of the storeroom door.

Jack is the depreciated dollar, the dull boy who kills the shine of Dick Halloran, and who attempts to kill the shine of Danny. Jack is the worthless paper dollar that will eventually collapse into the cold snow, and freeze to death in low temperatures created by the dollar’s murder of gold and the warm shine of the sun.