Banking practices in 18th century Britain are as captivating and romantic to me as a moor-set novel. The stories of Edinburgh’s competing bank houses in 1765 offer as much drama and intrigue as any feuding Georgian manor houses and, looking at the history, I can just imagine chemise-clad Regency women, fainting behind their kerchiefs, just as fearful of unregulated banks as they were of their own muscular servant gardeners.

What gives me a case of the vapors, myself, is that people rarely read these stories, even though these stories have absolute relevance to their own bank accounts. If more soccer moms, frightened by the idea of unregulated banking, understood how Scottish banking worked in the 1700s, they wouldn’t be at the mercy of predatory banks today, nor would they fall for (or, worse, support) all the banking regulations being pushed through Congress by the big banks, themselves.

The time period from 1716 to 1844 in Scotland was an era of “free banking” (or about as free as the planet has yet known): back then the Scottish government imposed very few regulations on banks and all the banks existing in and around Edinburgh and Glasgow were free to issue private currencies. (Today, we have corrupt laws against private currencies here in the U.S.)

These competing Scottish currencies were also sound or “hard,” meaning that every currency note was backed by gold or silver. Anyone holding a bank’s note could redeem it at the teller window for an equivalent amount of gold or silver bullion, usually in the form of coins. Paper currency back then was simply used to conveniently replace the handling of heavy coinage. (In fact, paper currencies emerged from the practice of the public’s trading their bank receipts for stored gold and silver nuggets.)

I like to think of hard money as a handsome suitor offering his consumer bride a ring of the gold that backs it. Hard-backed currency is the Mr. Darcy of the monetary world.

And who doesn’t like to watch attractive suitors compete?

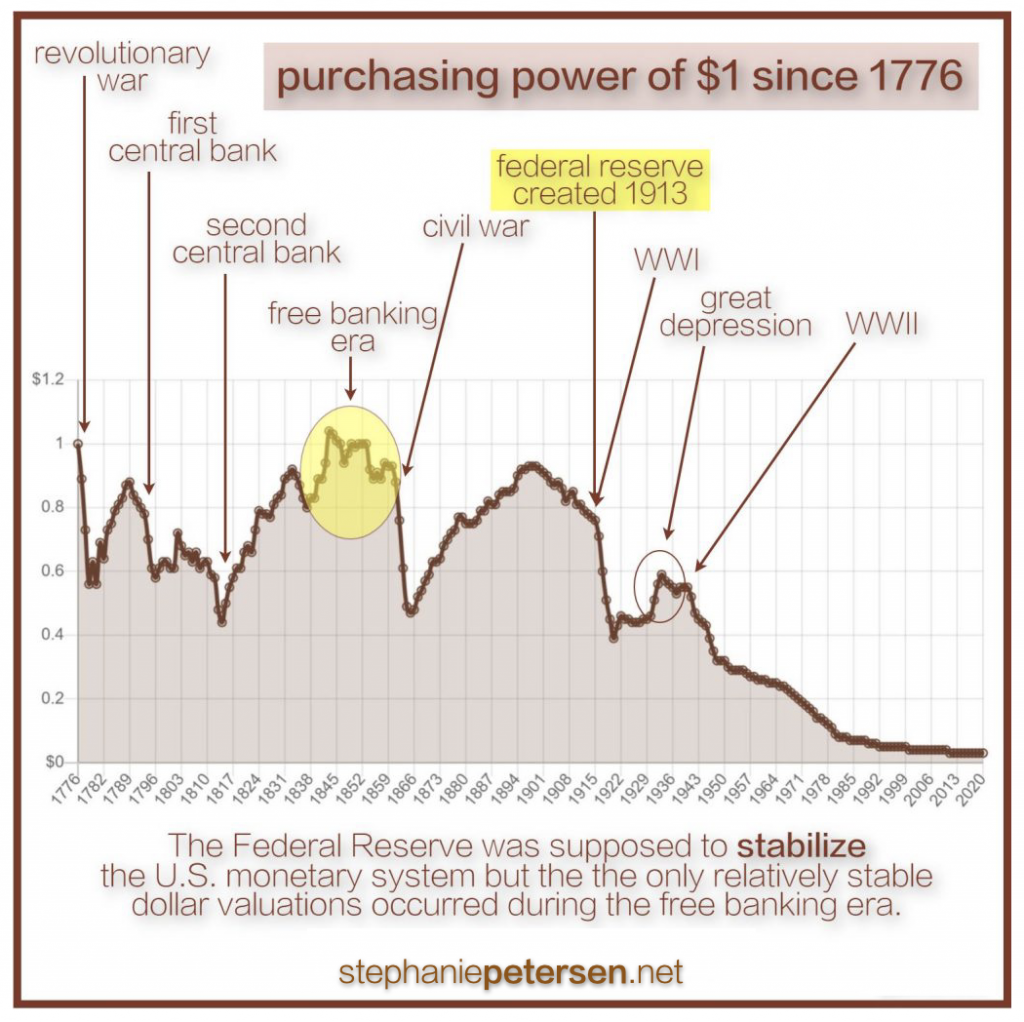

The benefits of competing currencies have been mostly lost to history, though crypto has revived their study somewhat. But here in the U.S., with the Federal Reserve holding a monopoly on the issuance of money since 1913, and the removal of that money’s hard backing by gold in 1971, most of our citizens have lost any understanding of the ways competing hard currencies can benefit the consumer.

We’re left with only George Wickham lounging around our parlor.

The primary argument against competing hard currencies has always been that private banks would print too much of their own money. But wait a minute, isn’t overissuance of money exactly the problem we’ve had with the Federal Reserve for over a century now? The Federal Reserve has over-printed dollars to such a degree that the value of a dollar has fallen over this time to a measly four cents. Of course, the “value” is still one dollar by law, but we see the true loss in its value as prices continually rise. What was worth a dollar in 1913 is today worth about four pennies, a loss of 96 percent of our purchasing power.

So we, the people, have been denied the freedom to enjoy competing hard currencies (and the preservation of our purchasing power and wealth) because the government is worried that we’ll date too many attractive men. I mean… that we’ll print too much of our own money. But that’s exactly what the government has turned around and done.

The government behaving like a controlling parent. Again. Now you see why I no longer vote.